Product Managers Take Note: Microsoft Is Using Serious Games To Product Test (And You Can Too)

Last Friday (September 17), I published a case study of Microsoft's Windows and Office Communicator (now Microsoft Lync) teams' use of "productivity games." What are productivity games? Put simply, they are a series of games produced by a small group of defect testers to encourage rank-and-file Microsoft employees to put software through its paces before it is released to the public. As many technology product managers can attest, getting employees of your company to take time away from their tasks to run a program in development and report any problems can be a Sisyphean effort: Bug checking doesn't have the allure of being an exciting, sexy job — but it happens to be necessary. It will come as a surprise, but since 2006, Microsoft has used five games to look for errors in Windows Vista, Windows 7, and Office Communicator; a sixth game — Communicate Hope — is currently in the field to test Microsoft Lync. Why so many games, you ask? Well, they work.

The most successful game Microsoft has launched to date is called the Language Quality Game. It was designed to get employees who could read languages other than English to check that the thousands of user interface translations Microsoft had made in Windows 7 were accurate. The game produced positive results on two dimensions: 4,500 Microsoft employees played the game, and this group had a total of 500,000 viewings of translated Windows 7 UI translations. Because the game went over so well, iterations of it have been used in Office Communicator and Exchange. And others at Microsoft are looking to use games to do other tasks: e.g., a group at Microsoft Office Labs has created a game called Ribbon Hero to encourage people to explore the functionality of the Office 2007 productivity suite.

For those of us who follow the use of games to accelerate business processes, this is not surprising. Well-designed games — with engaging problem sets (the fun aspect) and well-conceived incentives (e.g., leaderboards, prizes) — have convinced people to help businesses with difficult tasks in the past. For example, Google image searches are made possible, in part, by Google Image Labeler, a game that entices players to tag photographs by making it a timed game with leader boards (I highly recommend you give it a shot — the description isn't going to do it justice). Because games are engaging activities for people, a range a tasks have been proposed for them; Forrester has been studying this trend — called serious games, or the games to teach, provoke an attitude/behavoral change, or inspire an action — since 2008.

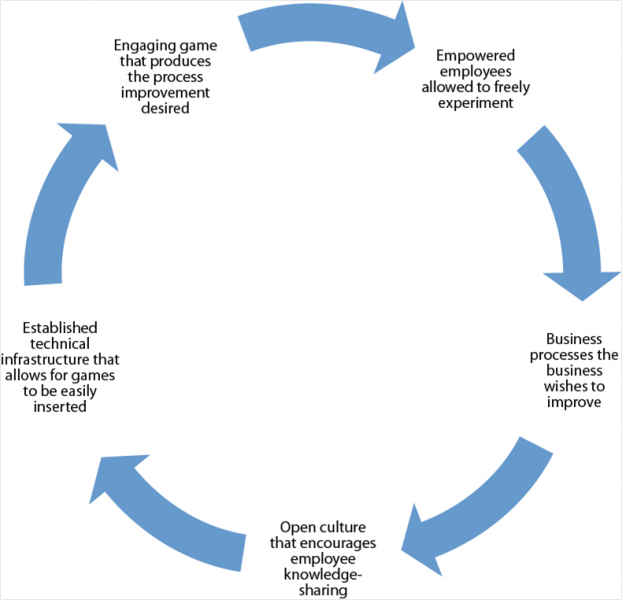

For product managers, there is a lesson here: Serious gaming can be a potent tool to get employees to help out on various product development tasks. Of course, getting a business to buy into this idea can take time. First, you need to understand why these games have taken off at Microsoft, which is summarized with this picture:

Microsoft encourages its employees to experiment with new ways of doing work and also moves its people around the company, allowing new ideas to spread. As employees who were involved with successful serious games joined new teams, they brought this knowledge with them; because the games were successful, these serious game developers were allowed to continue their work. In other words, this was a grassroots effort at Microsoft that is slowly becoming part of the mainstream. For product managers who are intrigued by the idea of using a serious game for product testing, ideation, concept testing, or other related tasks, the fact is that you're going to have to start small. So, as you think about heading down this path, keep a few things in mind:

- Assess whether or not you can actually create a game. A good game is a complicated thing to create because you have to get gaming dynamics — the problem set and the incentives for completing tasks — correct. So, you have to ask yourself what you know about game design. If these capabilities don't exist internally, you have to find them externally.

- Be prepared to be an evangelist. The guys at Microsoft who created productivity games were also the people who propagated its use. Ross Smith, a defect test manager and one of the serious games developers at Microsoft, has appeared on panels, written papers, and given presentations to promote this work.

- Keep the focus of the game narrow. The productivity game developers weren't trying to cure all of the world's problems — they were simply trying to get people to participate in product testing. Similarly, if you're looking to create a game, you have to identify the business you want to solve and keep the focus on that specific problem.