Taking Lessons From Smart Cities

On Sunday I will be participating in IBM’s Middle East and North Africa CIO Conference 2010, where I will present my research on Smart Cities. I’m looking forward to speaking with practitioners from the region to hear about their experiences in making their cities, organizations, and businesses more efficient through innovative technology-based initiatives. My presentation is entitled “Taking Lessons from Smart Cities,” because the real smarts lie in how these “cities” – whatever form they take – have overcome obstacles from budget battles to stakeholder standoffs.

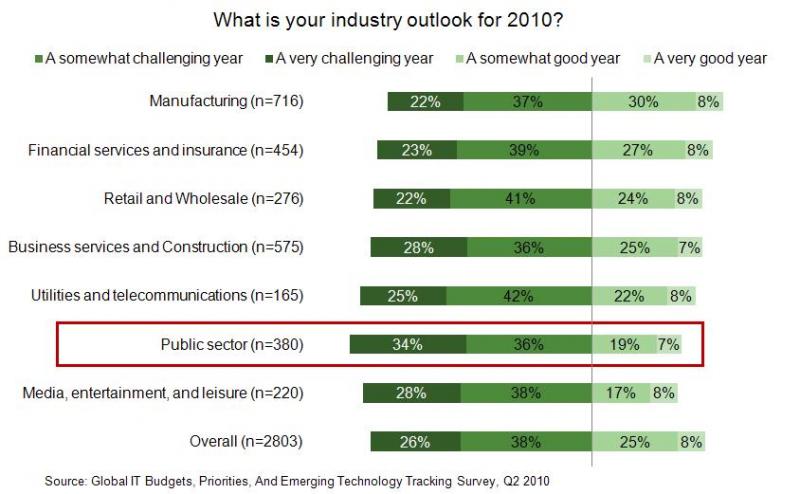

One aspect of those smarts lies in the business models that have enabled smart cities. With talk of municipal bankruptcy and public sector debt, it is not surprising that public sector IT decision-makers are not all that optimistic about their industry outlook. In Forrester’s Forrsights Budgets And Priorities Tracker Survey, Q2 2010, only 26% of public sector IT decision-makers considered their industry outlook to be good, while 70% – the vast majority – expected a bad year. The public sector came in next to last among other industry verticals.

One aspect of those smarts lies in the business models that have enabled smart cities. With talk of municipal bankruptcy and public sector debt, it is not surprising that public sector IT decision-makers are not all that optimistic about their industry outlook. In Forrester’s Forrsights Budgets And Priorities Tracker Survey, Q2 2010, only 26% of public sector IT decision-makers considered their industry outlook to be good, while 70% – the vast majority – expected a bad year. The public sector came in next to last among other industry verticals.

That same survey, however, also revealed expectations of IT spending increases in the public sector: 37% of public sector IT decision-makers expected IT budgets to grow by at least 5%; 11% expected increases of more than 10%. Some of that spending is creatively financed.

Several new business models have emerged to enable technology investment.

- External investment – Investments come from NGOs, regional development banks such as Asian Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, or country-level development banks such as Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). Investment in traditionally public sector initiatives is also increasingly coming from private corporations. Lavasa, a new city outside of Pune in India, is itself a corporation.

- Revenue-generating initiatives – Many cities start with initiatives that bring in revenues, which makes then self-funding (more appealing to tax payers and voters and more sustainable in tough economic environments). Several local governments have started with improvements in tax collection (Malaysia, South Africa); in others are fee-generating services like parking.

- Revenue-sharing agreements – Other cities are working with vendors and service providers to develop revenue-sharing agreements. Telefónica has worked with local governments in Latin America on m-parking solutions in which the cities pay a small up-front payment; then they share a percentage of revenues generated by the parking solution.

- Capacity reselling – Larger cities are investing in ICT infrastructure that can then be shared (for a fee) with smaller municipalities or other public sector agencies around them.

- Multicity initiatives –Working together with other cities or agencies enables smaller cities to undertake projects otherwise outside of their budget. Logicalis worked with 22 unitary authorities (district councils), health services, and the education organization in Wales to create a common broadband network. In another example, Southwest One, a joint venture set up between Somerset County Council, Taunton Deane Borough Council, Avon and Somerset Police, and IBM, enabled a common deployment of back office applications and customer facing services.

- Data monetization – One model that is less tested but has potential is data monetization. Allow developers to use the data collected by the different systems. Transport for London (TFL) has launched a data store allowing application developers access to all data they collect – traffic patterns, train arrivals, transfers, etc.

These new models enable more cities to invest in infrastructure and initiate smart programs.

My upcoming report will address these business models in more detail. And I welcome other examples of how we can continue to take lessons from smart cities.