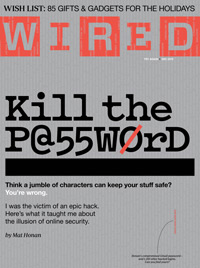

Make A Resolution: Kill Your P@55W0rD Policies

It has finally become hip not just to predict the demise of passwords, but to call for their elimination. The recent Wired article makes an eloquent case about the vulnerabilities that even "strong" passwords are subject to, such as social engineering and outright theft. And strength is, of course, relative and subject to degradation: The latest computer hardware can make short work of cracking more-complex secrets.

It's true: Static shared secrets are sitting ducks. But passwords are too useful to go away entirely, both because it's handy to be able to synchronize authenticator data between cooperating systems (and people), and because people find using passwords to be less invasive, fiddly, or personally identifying than a lot of other options. So I don't buy the whole "the era of passwords is over" thing. They will be at least one important element of authentication strategies for the foreseeable future — it's a rare multi-factor authentication strategy that doesn't include a password or PIN somewhere along the line as one of the "things you know."

So, if that's our reality, let's think outside the box in using them. In talking with Mike Gualtieri recently as part of his TechnoPolitics podcast series, I mentioned a few ideas. I had thought of these as pet password peeves, but on the cusp of 2013, why not be positive and think of them as resolutions?

Don't depend on passwords alone for sensitive operations. Leverage risk-based authentication (see our RBA Wave) to put multiple authentication factors into play in a way that inconveniences your users as little as possible. eCommerce and banking sites already do this heavily. By the way, how often have you changed your Amazon password? (I give my answer over in Mike's post.) When you accept passwords but don't bet the farm on them for assessing risk, funny things — funny good things — can happen to both risk management and usability.

Stop forcing users to thread the needle of your password policies. Password policies are well intentioned, but often misguided. Your goal in imposing them is to make users choose passwords that are harder to crack. Their goal is to defeat the unmemorability of the resulting string. This misalignment of goals means you get strings that pass your test but have limp-noodle bit strength because they're entirely predictable and already listed in dictionaries, like P@55W0rD — along with causing your users to swear and gnash their teeth. This great paper on password policy theater from Microsoft Research explains how "Much of the extra strength demanded by the more restrictive policies is superfluous: it causes considerable inconvenience for negligible security improvement." Why not pick your users' passwords for them by applying a random password generator? Some offer mnemonic help and settings for increased memorability, and you know everyone was writing down their passwords before anyway. Goal misalignment solved.

Consider "push" models for refreshing user passwords. People really, really hate changing passwords. That's because we've put the onus on them to do all the work: Go to some special app, choose a new password that meets the silly policies, and wait for it to propagate everywhere. And yet, if you do depend on passwords for significant risk mitigation, rotating secrets is one of the most important things you can do. As the Agile developers say, "If it hurts, do it more often" so that you can surface and fix issues. Interestingly, we already have a real-world example of passwords that are easy to refresh as often as we like: one-time passwords. They solve these issues by using a push model to send the secret to a user's previously registered alternate channel. What if we make it this easy to refresh users' "static" passwords, that is, passwords with a longer-than-momentary lifetime? Once we put ordinary passwords on the "refreshable" continuum, we've begun to shape a new future for passwords that isn't as bleak.