Seriously, Governments Should Be Playful

As we know, citizen engagement is a top priority of governments around the world. Many are launching digital outreach projects such as Adopt-A-Hydrant (pictured to the right). This is good news for both their citizen and business constituents (as well as for the application and platform vendors). Engagement is good. But what is really the best way to do it? What form should these projects take? How should the applications be designed? One way that has proven successful is the game.

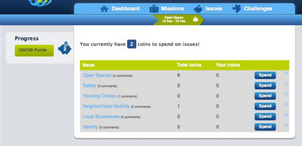

Recently, Rowan Curran, a research associate here at Forrester, attended a lecture at Harvard's Berkman Center for Internet and Society by Eric Gordon on Transforming Local Civic Engagement Through an Online Game. The lecture presented research on why governments should use games for engagement projects. For starters, games enable digital civic engagement projects to truly engage. As Eric Gordon put it in his lecture, too often “public feedback is conflated with engagement.” Reporting a streetlight out is not engagement. Engagement suggests holding someone’s attention, participation — not merely reporting. When people play a civic game, they are engaged. Recent research on implementing Community PlanIt — a game designed by Gordon's Engagement Game Lab — in Detroit and Boston found that people played because they liked the games. Games are fun and keep people engaged.

But who plays these games? Are they just a means to reach out to game-playing kids in the constituencies? Nope. Gordon’s research also shows that adults play too. And, interestingly, the presence of adults in a social/multiplayer community game lends a certain legitimacy to the game and encourages more young people to play. The presence of young people, in turn, encourages adults to play more and tempers behavior, as they are aware of their role as a model. That virtuous cycle creates greater engagement.

Design also contributes to success. A more tangible, goal-oriented design in civic games is more likely to succeed. Simplicity is key. Of the two projects implemented by Gordon's, Detroit was considered a greater success than Boston — although both had good participation. In Detroit, the goal of the game was to help the city decide on funding for specific projects. In Boston, the goal was to create a more abstract school-assessment framework. Boston has yet to agree upon the school-assessment metrics the game was supposed to help define. Lesson learned: Keep it simple.

Design also contributes to success. A more tangible, goal-oriented design in civic games is more likely to succeed. Simplicity is key. Of the two projects implemented by Gordon's, Detroit was considered a greater success than Boston — although both had good participation. In Detroit, the goal of the game was to help the city decide on funding for specific projects. In Boston, the goal was to create a more abstract school-assessment framework. Boston has yet to agree upon the school-assessment metrics the game was supposed to help define. Lesson learned: Keep it simple.

Governments can also increase engagement even before the project begins by putting the design into the hands of the community through hackathons. Hackathons are another way to bring young people into the process. By using hackathons as ways to ideate and outline applications for digital civic engagement projects, governments can also reduce their development costs and encourage the development of skills needed to drive an information-based economy.

So does this mean that all city- or state-level digital civic engagement projects should sport badges, virtual coins, and a leveling system? No, we've already learned that games and gamification is not a panacea. However, there are huge opportunities for governments to take advantage of games as engagement mechanisms. In some cases, the foundations are already there. For example, Boston’s Citizens Connect app (for reporting potholes and other issues) could be augmented with little trouble to include a set of leaderboards and other statistics for cooperative-competitive engagement. Opportunities abound. And, Rowan and I are planning research on citizen engagement through games. Thanks, Rowan, for sharing your notes on the lecture.

Game on!