Groupon: Scourge Or Phenom? Our Vote: Phenom. Here’s Why…

A Rice University faculty member just published a study on how effective merchants find Groupon. To Groupon critics, it was honey because a whooping 40% of participants wouldn’t repeat the experience.

But here’s the catch and why I’m still a huge proponent of the “group buying” model that encompasses Living Social, Buy With Me, Tippr and now the Yellow Pages and local radio stations and newspapers too: most of that 40% thought the Groupon customers were cheap and tipped badly.

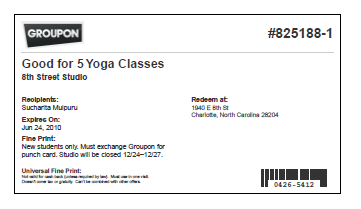

If that’s the worst of the problems, this model may actually be worth much more than the billion-dollar valuations already placed on the space. Here’s why. First, businesses like restaurants can prepopulate the “tip” field. I went to a restaurant in Charlotte called Zebra which has done multiple group buying offers and they include a 15% gratuity in the bill. Any business not already doing that could and should be. Second, and more powerful, is that the group sites could capture information on who is a good and bad customer from the merchant. Every redemption has a unique code associated with it (see image). None of the group buying sites are doing that now and merchants, at least according to the few that I’ve interviews, are keeping track of redemptions in rudimentary excel spreadsheets. The first company to provide a merchant tool that allows the flagging of particularly good and egregiously bad customers will be the winner in this space. By eliminating the “bad” customers from the offer, a merchant is much more likely to experience profitability or service issues that strain these small businesses.

There’s a lot of information about the individuals that the group buying sites are claiming is so important—their zip code, their mailing addresses, their preferences based on what they buy. What they’re missing is the single-most valuable piece of information that can drive a successful Groupon for their customers—whether or not that customer is a good one.