3-1-1 Meets Open Data: Open 311 Empowers Citizens and Extends Smart City Governance

In my last blog, I discussed the 3-1-1 initiative, which was in many cases the instigator for creating citizen services portals and a channel not only for delivering services but also for registering requests and complaints as feedback into the system. However, the interaction doesn’t stop there. Not only are cities soliciting feedback on citizen services, cities and other public agencies are now also providing data and APIs to enable citizen-developers to create applications themselves – bringing even the creation of citizen services directly to the citizens themselves.

I first wrote about this trend last year in "Open Cities, Smart Cities: Data Drives Smart City Initiatives." Such open data initiatives have exploded in recent years – with different terms for the same thing (naturally): open government data (OGD) in the US and public sector information (PSI) in Europe. Yet, with common standards: open data should be complete, primary, timely, accessible, machine-readable, non-discriminatory, non-proprietary in format, and license-free.

“Public” data is not just from the government, nor for the government

However, “public” data is not just from the government, nor only for the government (so “open data” is likely a better moniker than either above). I’ve been thinking about the idea of data for some time now as I see it as the biggest of the megatrends. At Forrester, we like to identify megatrends in the tech industry and postulate on the disruption they will bring. Think globalization, consumerization of IT, smart, cloud, etc. I’ve been thinking a lot about data. Everyone needs data: to inform a decision, to prove a point, to demonstrate the validity of a business model, to defend their interests, to convince someone of something, and so on. And, there is a ton of data out there, much of it “public.”

Data can be simultaneously “smart” and “social” (thus encapsulating both of those trends). We produce data through smart (technology-enabled) systems, but we also produce data ourselves . . . or people in general do. People offer up an increasing amount of data about themselves both implicitly (e.g., search terms, usage patterns) or explicitly through various online social activities such as tweet streams, Facebook status, LinkedIn profiles, online reviews such as Yelp, online personal finance tools, and now directly to the government through 3-1-1 initiatives.

As a result, my broader definition of “public” data includes:

- Government data sources (both public and private) – including data from government program results, statistical surveys, budgets, etc. Examples include:

- Data.gov and usaspending.gov (US public data)

- Data-publica (French public data)

- DataMarket (European and Icelandic data)

- tfl.gov.uk (London transport public data)

- Citizen data sources – including end users/citizens profiles, usage patterns, incident reporting, incidents, taking surveys, writing reviews, etc. Examples include:

- Open Spot for parking

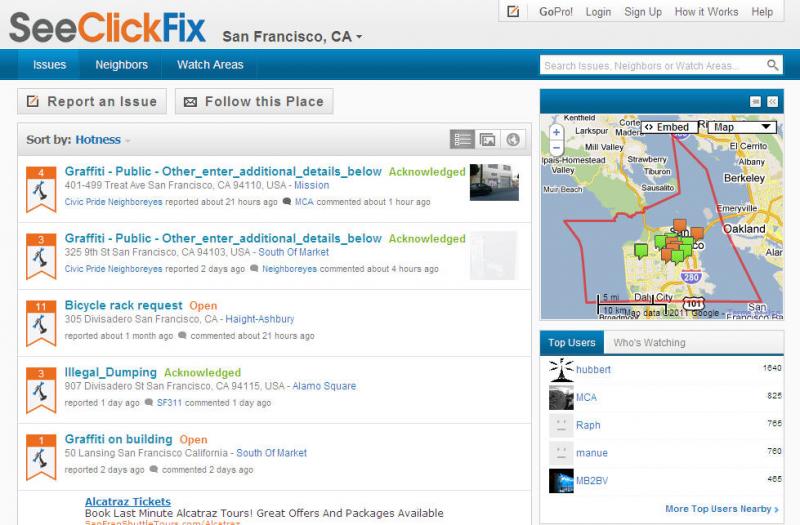

- SeeClickFix for city service or repairs

Both of these sources enable cities (counties, schools, or other public sector agencies) to better understand the results of their programs and enables developers, ISVs, or other citizens to develop additional citizen services. [As I wrote this, I was thinking that a Yelp review might not be particularly useful for a city government’s policy decisions. But, when I started digging around I found that Yelp actually does have discussions of policy issues, such as public sector employee benefits, and has even served as a model for reviews of veteran services.] Increasingly, these data are being put to good use to create applications that provide additional services to citizens.

Open 311 – announced by the US CIO Vivek Kundra on March 3, 2010 – brings together the open data initiatives and 311 system s. Open 311 provides standard and open APIs to explicitly facilitate the generation of citizen input or data and the use of citizen-generated data for development of new citizen services. By opening up the system, others can see the feedback and make additional comments – enabling cities to get additional information on reported issues. Developers can create applications that can feed data directly into 311 systems, and data from 311 systems can be used in other applications. And, ideally, those applications would be interoperable across 311 systems: whether the pothole is in Austin or Auckland. For example, FixMyStreet, an open sourced, Open 311 application, has implementations in the UK, Canada, and New Zealand.

s. Open 311 provides standard and open APIs to explicitly facilitate the generation of citizen input or data and the use of citizen-generated data for development of new citizen services. By opening up the system, others can see the feedback and make additional comments – enabling cities to get additional information on reported issues. Developers can create applications that can feed data directly into 311 systems, and data from 311 systems can be used in other applications. And, ideally, those applications would be interoperable across 311 systems: whether the pothole is in Austin or Auckland. For example, FixMyStreet, an open sourced, Open 311 application, has implementations in the UK, Canada, and New Zealand.

In the screen shot of SeeClickFix to the left, issues have been reported (including pictures), voted by additional viewers, and acknowledged by the city public works department.

In the screen shot of SeeClickFix to the left, issues have been reported (including pictures), voted by additional viewers, and acknowledged by the city public works department.

Cynics might call this crowd-sourced government. But in the US, government has always, in theory, been “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” Open 311 just enables the use of technology to fulfill that promise. Sounds idealistic? Perhaps. But, it’s happening already, and it’s only one year old, on Wednesday.

Tech vendors developing products and services for the public sector must take open data initiatives into account. MetricStream, for one, has added an Application Studio to its Governance, Compliance, and Risk platform to facilitate the development of governance applications. Other city governance platforms should do the same – and support the Open 311 APIs. Consider it a birthday present.