Fragmentation Is A Way Of Life, But Few New Platforms Will Emerge

In recent weeks, I’ve been asked the same question several times: Will the devices market continue on a highly fragmented path, or will the market shake out to yield a couple of viable form factors and platforms? This query actually encompasses two distinct questions, with two answers:

1. Devices and form factors will continue to fragment, though failures will abound.

Let me unpack this a bit, starting with some background: In 2007, I published a report called The Age of Style in which I predicted that computing form factors would diversify and fragment:

By 2012, the industry won't include just two form factors, laptops and desktops, but five or more form factors that are universally viewed as differentiated products.

The advent of new mass market computing experiences — from smartphones to eReaders to several flavors of tablets to phablets (and beyond) — rendered this prediction accurate. We live in a world of form factor diversity, which is only increasing with the introduction of wearables, the accelerating fragmentation of the tablet category, and the innovations associated with television-sized, collaborative touchscreen devices.

And each device tends to fill a specialized niche in users’ lives: Connected by cloud synchronization, storage, and sharing services, users are becoming adept and making trade-offs between devices. I can continue a work stream (e.g., editing a document) or personal digital activity (e.g., reading on my Kindle app) across multiple computing devices, starting on a PC or Mac, continuing on a tablet at the coffee shop, continuing again on a smartphone while standing in line at the store, etc.

I liken this to the history of the kitchen: 100+ years ago, households owned an icebox. That solution grew into a device: a refrigerator. Incrementally, people added a wide array of devices to the kitchen milieu, including a range, an oven, a toaster, a blender, a dish washer, a mixer, etc. There’s no specific limit (other than the size of the room) to the number of specialized devices that can be added; the kitchen is a socially-constructed concept, and it evolves over time. Similarly, our personal computing device lives are socially constructed, too. The increasing role of the cloud in orchestrating cross-device hand-offs is allowing additional devices to interoperate with existing computing devices.

Just as tablets have taken their place as a third mass-market computing form factor, others will continue to do so — as long as they provide value. My colleague Sarah Rotman Epps recently predicted that Google Glass can be the next iPhone when its technology matures. My colleague Ted Schadler pointed out the potential for additional specialized devices in workers’ (and consumers’) lives. The key in both cases is providing unique value in the computing experience. By the way, many of today’s experiments with new form factors will fail even as new concepts emerge continuously.

2. Only a few platforms can thrive — but several will do so.

Platform diversity is a little different from form factor diversity. Why? Because any given platform needs to attract software developers to support it with apps.

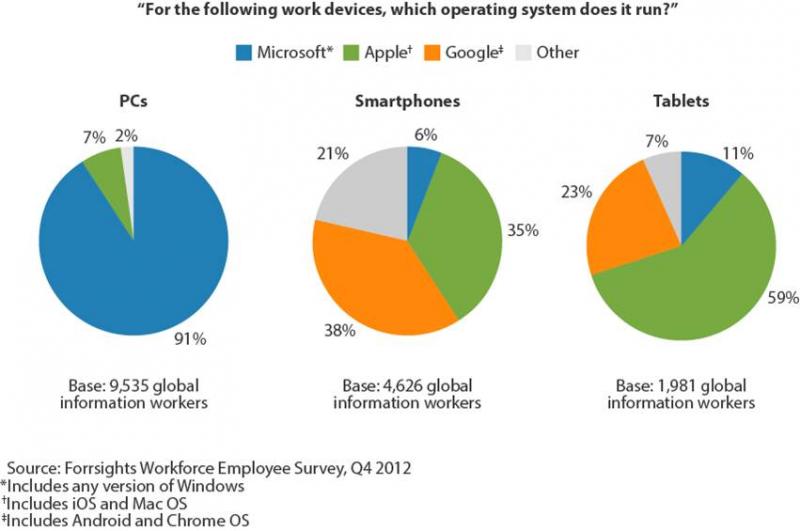

Today, different platforms dominate on different form factors, as data from our Forrsights Workforce Employee Survey demonstrates for information workers. But we see the big three — Windows, Android, and Apple’s iOS — capturing the lion’s share.

Figure: Platform Dominance Varies By Form Factor

So there’s platform fragmentation already, but how many more (net new) platforms can emerge? I would say very few. Why? Because:

- Few vendors have the resources to launch a new platform. Looking back at the recent graveyard of operating systems, we see how hard it can be to launch a new one (even a Linux-based OS that leverages existing developer talent). Intel (Moblin), Nokia (Maemo), Intel/Nokia (MeeGo), Palm (WebOS), HP (WebOS) … all these experiments yielded little. The only global player with pockets deep enough might be Samsung (which, to be fair, also has the Bada and Tizen operating systems in its pocket) — but Samsung seems content to dominate Android and participate in Windows.

- There’s a developer-defined limit to the number of client platforms that can coexist. But it’s a tough road, insofar as we’re discussing proprietary client platforms that require native apps to create the best user experience. The struggles that Blackberry (with its 10 OS) and Windows (with Windows Phone 8) have had getting developers to support their platforms the way they support iOS and Android demonstrate the challenge. While developers are moving to a scalable, cross-platform, omnichannel approach, native apps remain key to the success of iOS and Android. There just aren’t sufficient developer resources to create native apps for more than a handful of platforms (if that many).

- Cloud-based “platforms” using modern web technologies can continue to grow, however. The exceptions to this picture come in cases where the onus on developers is very low — where web standards like HTML5 create the experience, obviating the need for native apps. Chrome OS on Chromebooks, for example, leverages the same standards as the Chrome browser. FirefoxOS will empower devices to “run applications developed entirely using HTML, JavaScript, and other open web application APIs.”

So prepare for a world of platform diversity over the next three years. For Infrastructure and Operations professionals, CIOs, and others (even marketers!) who care about these issues, prepare yourselves for a world in which the current platforms persist (Windows on PCs; Apple’s iOS on phones and tablets; Android on phones) and grow (Windows and Android on tablets). Where new platforms emerge, they will be related to radically different experiences (like Google Glass) or the aforementioned open standards (Chrome OS, FirefoxOS). Brace yourself for a world of platform diversity — but not platform chaos — over the next three years.