Value For Customers: The New Frontier For CX Professionals

Most firms love to talk about the value of customers but don’t get value for customers right. That’s ironic because customers that get value create business value in return by increasing profitability and market share. Academia has written about value for customers for decades. But businesses have been sluggish and incomplete in applying it.

We asked ourselves: Why is that? How can we do better? What can companies gain if they understand value for customers? What is a customer experience (CX) pro’s role in this?

To answer these questions, we kicked off a new stream of research. Our first report, “Value For Customers: The Four Dimensions That Matter,” introduces Forrester’s framework. To write this report, my terrific colleague Shar VanBoskirk and I came together and tackled the topic from a marketing and CX perspective. In the report, we define four dimensions of value for customers, correct three troublesome misconceptions, and share examples that companies can model to improve value for customers (and themselves), including Amazon, L.L. Bean, Rugged Maniac, Sage Software, and USAA.

The Truth About Three Value-For-Customers Misconceptions

People assume they know what “value for customers” means but misunderstand the term! Our research found three problematic misconceptions about the what, how, and who of value. These misconceptions obstruct a firm’s ability to increase value for customers.

1) Misconception (“What”): Value For Customers Is About Value For Money

Value for customers is actually “customers’ perception of what they get versus what they give up.” Value can be created (or destroyed) in four dimensions:

–> Functional: Purpose is fulfilled (or impeded).

–> Economic: Money is saved (or spent).

–> Experiential: Interactions and sensations are pleasant (or unpleasant).

–> Symbolic: Meaning is created (or destroyed).

Siloed efforts by marketing, CX, product, sales, or pricing fail to create value across all dimensions. Worse, lacking a horizontal view of the customer, these efforts can cancel each other out.

Customers make tradeoffs between these value dimensions. They are willing to give up value in a less important dimension if they get high value in another, more important one. But customers have a threshold for how much they are willing to give up depending on their context. For example, take customers who stopped using Uber despite its ease (high functional value) and low fares (high economic value). Why? They heard the troubling news about driver conditions and other issues. And because of their strong views on these matters, using Uber meant sacrificing too much symbolic value.

To differentiate from competition, companies look to improving experiential value and/or symbolic value for customers. For example, banks redesign their branches to create experiential value through more pleasant sensations and interactions. Patagonia and Chick-fil-A create symbolic value by creating meaning for customers who want to buy from a firm aligned with the values these customers live by. Patagonia foregoes revenue by encouraging people to buy used and repair damaged clothes instead of buying new items to minimize the environmental impact of discarding old products and manufacturing new ones. And Chick-fil-A has an unapologetic “closed on Sundays” policy based on its founder’s and employees’ values. Read more on Forrester’s research on these companies here and here.

2) Misconception (“How”): Features Of A Product Or Service Create Value For Customers

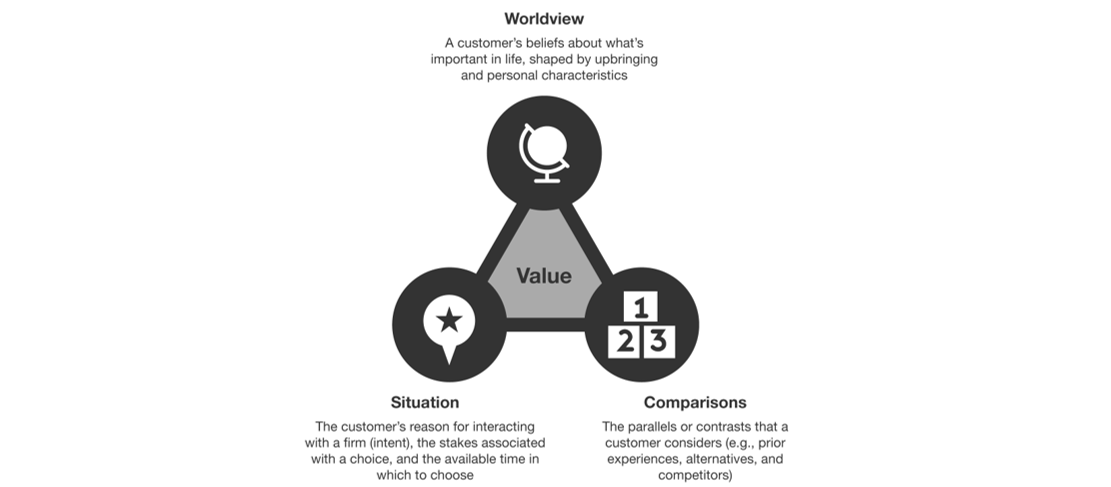

Value isn’t inherent but a perception. Context (worldview, situation, and comparisons) determine what customers value and how they form that perception.

Let’s look at what two different customers value — we’ll call them Bill and Amy — using Netflix’s streaming service vs. its DVD shipping service. Bill lives in an area with a good internet connection and wants to watch something entertaining right now (situation). Bill is not picky about what to watch (worldview). And he subscribes to other OTC services (comparison). Bill gets high value from Netflix streaming services. Contrast that with Amy. Amy is a discerning movie buff (worldview). She also lives in an area with a poor internet connection (situation). That’s why Amy gets low value from streaming. Amy signs up for the DVD service to get access to more titles independent from the quality of the internet.

To form value perceptions, many people use “mental shortcuts,” especially when they are under time or pressure or unfamiliar with a product or service. For example, if Bill and Amy were planning a vacation together but running out of time to select a hotel, they might just follow their friend John’s recommendation. With more time to decide, Amy and Bill would instead create a list of pros and cons for different options.

3) Misconception (“Who”): Your Firm Creates And Delivers Value For Customers

When trying to accomplish a goal, a customer derives value not from interacting with a single firm but from her own actions and interactions with many different organizations and people. For example, to become healthy, a customer creates a value network that includes a doctor but also a physiotherapist, friends and family, associations, and insurance firms — getting different value from each. Forrester refers to these relationships as a value network.

Firms that understand customers’ value networks and what value they seek from the firm vs. other actors can help customers create more value. For example, US financial services firm USAA has top CX and incredibly high customer retention. USAA helped customers create value by taking on elements of their value network: For members who want to buy a car, USAA had developed its mobile-accessible Auto Circle car-buying service that helps members get a car they can afford. Using Auto Circle, members can apply for financing with USAA, gain easy access to car search functionality — via USAA’s partnership with TrueCar — and get connected to trustworthy, USAA-certified dealers.

CX Professionals Must Step Up To Improve Value For Customers

CX pros have the horizontal view of the organization along customer journeys. That’s critical to understanding what customer want to accomplish, who they interact with as they do, and what value they want from each actor — inside and outside your firm.

If you are a CX pro, volunteer to help your firm to improve value for customers! Get started by understanding how well your firm helps customers create value, then define metrics for value for customers and focus your research and design practice on identifying what customers value and find ways to help them create it. Finally, pivot your CX ecosystem to help customers create (rather than destroy) value.

Future reports will be about those topics, and we want to hear from you! Please share your questions or examples with us to inform the research.

On that note: I am glad to report that we see others actively working on creating more awareness of value for customers. For example, check out the work by Gautam Mahajan, who founded the Creating Value Alliance and started a conference on value to bring academics and business leaders together to discuss and foster value creation.